Wild Capitalisms:

The political ecology

of the post-socialist

city from pyramid

to ppparadise

By Michał Murawski

1 July 2020

Since the collapse of state socialism in 1989-1991, cities in the post-socialist world have experienced two types of anti-urban unravelling. The centrifugal chaos of the 1990s-2000s (urban depopulation, mass unemployment, hyper-inflation, the rise of urban subsistence agriculture, an explosion in organised crime, everyday violence and fraudulent get-rich-quick pyramid schemes) is often referred to as the time of “wild capitalism”.

Paradoxically, although during this time the cities of Eastern Europe did indeed begin to dissolve into the countryside, the architecture – with certain exceptions – of the first wild capitalist city (c. 1989-2010) was characterised by a striving for urbanity, monumentality and uprightness. Among the most illustrative symbols of this early wild-capitalist will-to-verticality are the hundreds of vernacular postmodern pyramids (kiosks, restaurants, shopping malls, public facilities) which sprouted up through the post-socialist world during this period.

Today, post-socialist polities like to believe that they have settled into a more “civilised”, “normal”, less savage form of capitalism. There is no doubt that levels of everyday violent criminality have decreased in most parts of the post-socialist urban world since their 1990s heyday. However, precisely what this maturity consists of is difficult to define. Cities continue to be torn apart by brutal and unchecked processes of land and property restitution and reprivatisation, speculation, stratification, segregation, de-planning, waste crises and assorted ecological catastrophe. The time of wild capitalism, I would like to suggest, is far from “over” in the post-socialist world. In fact, this term can now be productively unanchored from its post-socialist origins and used to make sense of the political economy, ecology and aesthetic of the 21st century global (urban) condition. The architectural aesthetic of the second (global) wild capitalist city (c. 2010 onwards), however, has now shifted from the pyramidal to the paradisiacal. From Moscow to Kigali, New York to Singapore, the deeper we sink into the depths of our anthropocenic techno-dystopia, the more spectacularly bucolic, lusciously Edenic, superlatively nature-tectural (“agritectural”, in Elizabeth Diller’s phrase) our cities aspire to become.

The Age of the Pyramid

February 20, 2016 in Moscow was nicknamed the Night of the Long Diggers: hundreds of temporary structures, kiosks and micro-shopping centres throughout the city – primarily those abutting metro stations – were summarily demolished in a brutal fit of urban prettification. Aftershocks of the Night of the Long Diggers continued for several weeks. February 24 saw the demolition of the “Piramida” shopping complex on Pushkinskaya Square, in the very heart of Moscow (Fig. 1a-b).

Fig. 1a PiraMMMida demolition

Fig.1b

This doomed pyramid, erected in 1997-1998, recalled a time – in the commentary of a Russian TV newscaster chronicling its demise – “when the word capitalism brought to mind the epithet ‘wild’, when criminal empires hid behind what appeared to be absolutely respectable contours”; a time during which chaos reigned or was perceived to reign in the post-socialist world (Fig. 1c). 1

Fig. 1c Pirammmida Wild Capitalism

So what the style of the wild capitalist era; and how did this style manifest itself in the life of the city? How did this relate to the way in which politics and economics were done (what, in other words, was the political aesthetic and the economic aesthetic of wild capitalism); and when – if ever – did the time of wild capitalism come to an end?

This was the time of the Moscow reign of Mayor Yuri Luzhkov, during which the Mayor’s wife, property developer Elena Baturina, became a billionaire, allegedly thanks to municipal tenders handed to her by her spouse; when criminality, gun violence and banditry reigned rampant in the streets; when healthcare collapsed and mortality skyrocketed; and when – in a vain attempt to paper over the pervasive madness and desperation with an illusion of order, prosperity and uprightness, as embodied in the so-called “Luzhkov style” – elaborate, shiny temples, monuments, billboards and images of glamour and excess filled the city. This is also a time when pyramids, especially glass structures paying homage to Las Vegas’ Luxor Hotel (1993) or IM Pei’s Louvre pavilions (1983), proliferated throughout cities in Russia and elsewhere in the post-socialist world (Figs. 2).

Fig. 2a Kazan

Fig. 2d Rostov

Fig. 2f Chelyabinsk

Fig. 2i Chelyabinsk

Fig. 2k

Fig. 2o Tbilisi

Fig. 2s Astana

Fig. 2b Kazan

Fig. 2g Chelyabinsk

Fig. 2h Chelyabinsk

Fig. 2l Vitebsk

Fig. 2p Voronezh

Fig. 2c Donetsk

Fig. 2e Minsk

Fig. 2j Zelenograd

Fig. 2m Vitebsk

Fig. 2n Gomel

Fig. 2q Gelendzhik

Fig. 2r Crimea Yevpatoriya

Examples include а monumental concert hall and restaurant in Kazan , capital of the Russian Federal Republic of Tatarstan (1997); the “Millenium” café in Donetsk, eastern Ukraine (1998); the folly-like studio of the architect Gaik Gulyants on Rostov-on-Don, western Russia (1994); the glass pavilion adjacent to the Soviet-era Univermag department store in the Belarusian capital, Minsk (late 1990s); the Sinegorye shopping mall in the Siberian city of Chelyabinsk (2002); a high-tech “water art” installation titled “Four Seasons” on a housing development in the Moscow satellite city of Zelenograd (2019); an elaborate, multi-storey lighting fixture on a housing development in the city of Barnaul, in the south-west Siberian Altai region (2018); the lion-flanked Marko City business centre in Vitebsk, Belarus (2012); a cluster of four pyramids marking the entrances to a pedestrian subway on either site of Sovetskaya Street in the centre of Gomel, Belarus (2015); and a see-through, corruption-deterring police station in Georgia’s capital Tbilisi, erected during the reformist reign of President Mikhail Saakashvili (2004-2013). There are many more: Voronezh, Gelendzhik, Evpatoria, Astana, the list goes on.

As the instances above show, the post-socialist enthusiasm for pyramidal forms has lingered long beyond their 1990s heyday; and many pyramids house functions which deviate from routine wild capitalist preoccupations. A pyramidal aesthetic overlaps with a paradisiacal function in the orangery of Minsk’s botanic garden (2007); while the fate of the “Moon Stone” café on Krasnaya Street in Krasnodar (precise opening date unknown) provides a case study in transitional pyramidalism (Fig. 3).

Fig.3a Minsk

Fig. 3b2 Krasnodar after

Fig. 3b1 Krasnodar before

Krasnodar’s long-serving pyramid cafe was briefly closed and disassembled in 2018; only to be reconstructed the following year, complete with remodelled eco-facades. As Krasnodar’s Kuban News reported, “the city authorities believe that the greening [of the pyramid] will allow for the café, situated on the central boulevard of the city, to be endowed with a refined, contemporary appearance”.

As real-life pyramids sprouted up throughout post-socialist towns and cities, private finance, too, became suffused by vertical forms, in the shape of what came to be called pyramid and/or Ponzi schemes (depending on their precise structure): get-rich-quick populist investment programmes, which promised to level the financial playing field for the benefit of those who were not capital rich; but, which – in effect – benefited only those who founded them, or the very early investors at the tip of the triangle. The most famous of these schemes, which came to be symbolic of the wild capitalist epoch in post-Soviet Russia, was MMM, founded by mathematician turned eccentric financial kingpin Sergey Mavrodi; and named after the initials of its founder, his brother Vyacheslav and their business partner Olga Melnikova. Famous for its alluringly relatable TV commercials, which mimicked the form of a mini-series chronicling the changing fortunes of an ordinary Russian family, MMM managed to sustain its activities for over a decade.

After a an extended (partial) hiatus, (and some bouts of time in prison and in parliament), Mavrodi relaunched his operation (now re-acronymised as Mavrodi Mondial Moneybox) on a global scale in 2011. MMM re-born, Mavrodi claimed, now took the form of a “social-financial network” and “mutual aid scheme” dedicated to “eradicating poverty”, formed by and for people who rose up against financial slavery”. Increasingly MMM focused its activities on Africa, Asia and Latin America; and by the mid-2010s had turned its attentions to Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies. It is widely suspected that Mavrodi’s machinations were responsible for the Bitcoin surge in 2015; and likely also for its disastrous crash in 2018 – the year of the founder’s eventual passing.

Throughout its activities, MMM Global place a relentless, unending rhetorical emphasis on its self-avowedly horizontal, non-hierarchical, altruistic nature. In the words of a rambling 2017 manifesto authored by Mavrodi (also circulated in the form of a hyberbolic, thirty-minute long propaganda video on MMM’s YouTube channel), “MMM is a financial social network … it is not a pyramid scheme” (Mavrodi 2017).

So when is a pyramid not a pyramid? Asked to comment on the demolition of the Pushkinskaya pyramid by the newspaper Afisha Daily, Mavrodi said: “An entrepreneur in Russia has to know not only whom to bribe, but also to know that the person they are bribing will hand over a part of their bribe to a more high-ranking official. This is also a pyramid of sorts.”

See Joanna Kusiak. 2018. Chaos Warszawa: Porządki Przestrzenne Polskiego Kapitalizmu. Warsaw: Bęc Zmiana, 2018.

For more insight on the wild capitalist shapes and styles of the Luzhkov era, see Bruce Grant. 2001. “New Moscow Monuments, or, States of Innocence”. American Ethnologist 28(2): 332-362; Daria Paramonova. 2014. Griby, mutanty i drugiye: arkhitektura ery Luzhkova. Moscow: Strelka Press; Konstantin Akinsha, Grigorii Kozlov, Sylvia Hochfeld. 2007. The Holy Place: Architecture, Ideology, and History in Russia. New Haven: Yale University Press; Bart Goldhoorn and Philipp Meuser. 2006. Capitalist Realism: New Architecture in Russia. Berlin: DOM Publishers.

On MMM Bank, see Eliot Borenstein. 1999. ‘”Public Offerings: MMM and the Marketing of Melodrama”. In Consuming Russia: Popular Culture, Sex, and Society Since Gorbachev, edited by Adele Marie Barker. Duke University Press. For an in-depth ethnographic study of the functioning of pyramid schemes, see John Cox. 2018. Fast Money Schemes: Hope and Deception in Papua New Guinea. Bloomington, IN.: Indiana University Press.

The Age of PPParadise

So, is the time of “wild capitalism” (and of pyramids) behind us? Has the post-socialist world stepped into a more “mature”, stable, predictable form of political economy (and political aesthetic)? “Wild capitalism” is very much a laypersons’ term, used for the most part by ordinary people or journalists; and it remains relatively untheorized and unanalysed. Its end point is difficult to pinpoint. The Night of the Long Diggers – orchestrated by the charismatic populist Luzhkov’s successor as Mayor, sullen technocrat Sergey Sobyanin – was one of the symbolic events of the erasure of the remains of “wild capitalist” Moscow and its replacement with a new, more “civilised” metropolis. One in which every inch of space need not necessarily be squeezed for profit; and one in which – in the official discourse of the city – space which is formerly private is returned to public use, for the public good. This is the new city of blagoustroistvo – an untranslateable Russian concept (literally meaning something like “the construction of wellbeing”), which refers to the prettification and improvement of urban public space and infrastructure. In the words of another reporter on a municipal news channel commenting on the demise of the Pushkinskaya pyramid: “there will be no new capital investments on the site of the demolished pyramid; the territory will be improved (blagoustroyat) for the benefit [literally, for the delight] of Muscovites.”

Indeed, Moscow in the second decade of the 21st century has been seized by an extraordinary wave of blagoustroistvo. Notably, Mayor Sergey Sobyanin is frequently presented today as an Empress Catherine-like “gardener” or “greener” of the city (ozelenitel), who has turned Moscow into an Edenic garden, and to whom the Muscovites ought to be grateful to for his fecund labours. (Fig. 4)

Fig. 4a Sobyanin ozelenitel

Fig. 4b Sobyanin ozelenitel

The most visible element of Sobyanin’s re-election campaign for the September 2018 Mayoral elections consisted of a series of posters showcasing the post-facelift appearance of Moscow’s streets and public spaces – chief among them the brand new, multi-billion-rouble, Kremlin-abutting Zaryadye Park, opened one year previously by Vladimir Putin. “Moscow is now even more beautiful (Moskva Eshche Krasivee). Sergey Sobyanin”, the images proclaimed. “This past year seemed to have produced a bountiful harvest of new parks and urban spaces – 81 green spaces have been built or have undergone blagoustroistvo in Moscow”, observed Sobyanin’s interlocutor in an interview printed in the tabloid newspaper Argumenty I Fakty several weeks ahead of the municipal elections. The Mayor concurred: “All of these parks are not only good, they can compete for the most prestigious international prizes. And, most importantly, they were made together with Muscovites, with love and with care for them.”

On September 9, 2018 – the day of Moscow’s most recent Mayoral elections, (not-so) coincidentally held on City Day (Den Goroda), the capital’s annual birthday party – the main avenues of the capital were cordoned off from traffic and transformed into paradisiacal islands of plenty. Muscovites lounged around on inflatable beds of greenery and photographed each other at specially-designated selfie-spots, marked by photographs of Zaryadye Park stuck onto the surface of Tverskaya Avenue. Children immersed themselves in playball pits decorated with the trademark green-white livery of the blagoustroistvo campaign. This temporary greening of the city was organised within the framework of the «Цветочный джем» (Flower Jam) festival, which lasted from 30 August until the 9th September (during which time extravagant firework displays were held daily over the Kremlin). According to the festival’s official description, proceedings consisted of:

“hundreds of master-classes devoted to botanical and floral science… guests learned how to fashion their own eco-creations and objects of décor, and took part in free excursions, devoted to the parks, gardens, squares and natural landscapes of Moscow. The culmination of the festival was the amateur flowerbed competition on City Day [Election Day]. Under the guidance of professional gardeners, Muscovites created more than 1,500 unique flowerbeds throughout all the districts of the capitals”.

The flagship project of this unprecedented blagoustroistvo drive is Zaryadye Park – a grandiose, high-tech hybrid parkscape opened in 2017 by Vladimir Putin on the site of the demolished 1960s Hotel Rossiya; and snidely referred to as “Putin’s paradise” (putinskiy ray) by its critics (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5a Zaryadye, by Michał Murawski

Fig. 5b Zaryadye meme by Michał Murawski

Fig. 5c Zaryadye, CC BY from Kremlin.ru

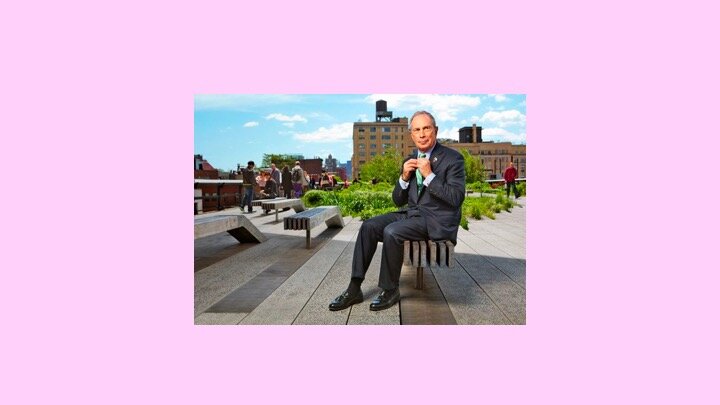

Zaryadye was framed, for public consumption, as a spontaneous “gift” from Vladimir Putin to the people of Moscow; and designed by the fashionable Manhattan architectural practice Diller, Scofidio + Renfro (DSR), who reached starchitectural prominence with Manhattan’s High Line – incidentally, a project also prominently framed as from as a gift from then-Mayor, oligarch philanthropist Michael Bloomberg, to the people of New York (Fig. 6).

Fig.6a

Fig.6b

Despite both the High Line and Zaryadye appearing to be sites of sovereign benevolence, where order is forged from chaos, they are each also endowed with quite intriguing ideologies of wildness and rurality. For the High Line, DSR developed the guiding idea of agri-tecture (this was in fact the name of the studio’s 2004 competition-winning entry for the High Line project): “part agriculture, part architecture” (Fig. 7, video file).

The High Line’s agritectural body emerges from its “long paving units – or planks”, which “have tapered ends that comb into planting beds to create a textured, pathless landscape, where the public can meander in unscripted ways”. In Moscow, agri-tecture morphed into the idea of “wild urbanism”, also defined in terms of a posthuman symbiosis between nature and the city; and in terms of its supposedly “pathless” and “scriptlessness”. As Liz Diller, Ricardo Scofidio and Charles Renfro enthused in a promotional video accompanying their 2013 competition entry for Zaryadye, “wild urbanism is park for the people It’s also a park for the plants. Plants and people have equal status” (Diller). “Wild urbanism is pathless. People are not told where to walk. Plants flourish everywhere. People and plants share the same surface” (Scofidio). “Wild urbanism makes a raw interface between buildings and landscape. Nature makes an abrupt edge with the city” (Renfro). (Fig. 8, video file)

There is an extraordinary rhetorical premium placed on the supposed pathlessness of Zaryadye – which brings to mind Mavrodi’s virulent insistence on the horizontal and transparent nature of his pyramidal undertakings. During the opening ceremony in September 2017, Charles Renfro gave a speech in which he unceasingly re-stated the imperative for users to wander astray within the park. Park visitors should “lose themselves in moments of repose”; “you can lose yourself amid the trees and in the water and in the mist”; “you can lose yourself amid the green and forest”; “it’s a park where you can lose yourself and it’s a park where you can find yourself again and find Moscow anew”. The intensity of this compulsive focus on pathlessness and indeterminacy is noteworthy, given the manner in which, in practice, both Zaryadye and the High Line prescribe and dictate pre-designed, pre-calculated walking trajectories – as well as visitor itineraries – for their users in a way that, arguably, very few parks of the old, non-wild urbanist kind did. As the Director of the park’s administration, Pavel Trehleb explained to me: “the services [provided by the park] allow visitors to complete a unique pathway [unikalny marshrut – lit. “marching route”] and experience a series of awesome emotions in an average time of just 2-3 hours!” This 2-3 hour marshrut is not, in fact, the only one, he qualified. There are, in fact, a series of visiting “cycles”, which have been “programmed into” the park, lasting “from a minimum of one and a half hours … all the way up to an entire day.” This kind of intricate visitor programming is necessary and essential, Trehleb insisted, because “for the brain it is very important that you find yourself constantly within some sort of external impulses which constantly nourish our emotional system.”

Zaryadye’s rhetorics of wildness, freedom, pathlessness and spontaneity are, I am insinuating here, somewhat spurious. Zaryadye – like the High Line – is hyper-sanitized, hyper-surveilled, hyper-controlled and policed, both on the level of coercive, external control; and on the level of internal (and digital) discipline. The High Line and Zaryadye are private-public paradises (PPParadises), spun – their horizontal, grassroots aesthetics notwithstanding – within a web of hierarchical dependencies on benevolent sovereigns and/or benevolent philanthropists. They are both distinct but commensurable variations on the hegemonic PPP (public-private partnership) model of financialised capital investment. The High Line functions by means of Private → Public Parasitism, in which government – in the case of the New York municipality, at the time of the High Line’s inception actually controlled by oligarch Michael Bloomberg – grants the bulk of the financing, while the private sector reaps almost all of the rewards and poorer New Yorkers suffer the effects of turbo-gentrification.

Zaryadye, meanwhile, functions as a public → private protectorship, in which the private sector provides a substantial part of the initial financing and reaps some dividends. In the case of Zaryadye, the private part of the partnership was embodied, at first, in the figure of the eccentric billionaire Dmitry Shumkov, who, in 2013, bought the plot of land on which a seven-star hotel is currently being built in the north-east corner of Zaryadye, for an estimated 8 billion roubles; thereby providing the city with the bulk of the financing for the park’s construction. Two years later, in November 2015, Shumkov was found hanging from three neckties in his luxury apartment in a Moscow skyscraper. In traditional wild capitalist fashion, ownership of Shumkov’s plot – which also includes Zaryadye’s gastronomic facilities – was thereupon transferred to the property developer Kievskaya Ploshchad, Russia’s largest and most politically-connected developer.

4. A compilation of all of MMM’s early 1990s advertisements is provided at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nRwkPts0vXY [accessed 16 June 2020].

5. See Izabella Kaminska, Dan McCrum and Robin Kwong. 2015. "Bitcoin surges as Chinese flock to Russian fraudster’s site". Financial Times, November 4; Claire Brownell. 2015. “The Russian ex-convict's viral financial scheme that might be behind Bitcoin's surge”, Financial Post, November 6.

6. See the 2017 document authored by Ardi Prabowo (most likely Mavrodi himself), “The Ideology of MMM Global”, available at various locations online including https://www.academia.edu/34444481/Ardi_Prabowo_MMMGLOBAL.COM [accessed on 16 June 2020]; as well as the associated video published on MMM Global’s YouTube channel, https://youtu.be/tAAcDCle20A [accessed 16 June 2020].

7. For more background on blagoustroistvo in contemporary Russia, see Michał Murawski. 2019. “Repairing Russia”. In Repair, Brokenness, Breakthrough: Ethnographic Responses, edited by Francisco Martínez and Patrick Laviolette. London: Berghahn; Michał Murawski. 2018. “My Street: Moscow is Getting a Makeover, and the Rest of Russia is Next”. Calvert Journal, 29 May; for commentary on the functioning of blagoustroistvo in Stalinist Russia see Heather DeHaan. 2013. Stalinist City Planning: Professionals, Performance, and Power. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

8. For more on Catherine’s gardener personality cult, see Stephen Baehr. 1991. The Paradise Myth in Eighteenth-Century Russia: Utopian Patterns in Early Secular Russian Literature and Culture. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press; Andreas Schönle.. 2007. The Ruler in the Garden: Politics and Landscape Design in Late Imperial Russia. Oxford: Peter Lang.

9. Elizabeth Diller. 2014. “Agri-tecture”. In The Return of Nature: Sustaining Architecture in the Face of Sustainability, edited by Preston Scott Cohen and Erika Naginski. London, New York: Routledge, p. 170.

PPParadise is a Pyramid

Of particular significance is the way in which the English term “wild urbanism” was translated into Russian. Initially, the term “dikiy urbanizm” (lit. wild urbanism) was used, but this swiftly morphed in official materials connected to the park design into “prirodny urbanizm” – which means something closer to natural urbanism. As my Moscow interlocutors – those connected to the implementation of the park design – told me, this was explicitly done in order to foreclose any connotation of “wild capitalism” – “wild capitalism” being precisely the chaos that Zaryadye was supposed to be a symbol of the victory over; and of the erasure of.

Wild capitalism lives on in Sobyanin’s Moscow, in Bloomberg and De Blasio’s New York, in Johnson and Khan’s London. “While people in Eastern Europe were busy complaining about ‘wild capitalism’ and dreaming of coming closer to the ‘civilized’ west”, wrote Russian Marxist sociologist Boris Kagarlitsky in 2007, “western capitalism itself was only getting wilder”. 21st century late capitalism is indeed today as vicious, criminal, de-humanising and pyramidal as it ever was; at the same time, however, capitalism has become extremely adept at endowing itself with legitimacy by adopting the anti-pyramidal rhetorics and aesthetics of horizontal, self-organizing social movements; as well as of ecological art, activism and theory. The term “greenwashing” first appeared in the 1980s to refer to the hollow environmental claims made by corporations; today, spurious ecologism and ersatz horizontalism are in overdrive. The cod-ecological sustainable utopias of the 1990s and early 2000s are slowly being realised – reaching their grotesque apogee not only with the High Line or Zaryadye (and their multiple clones); but with next-level indulgences, such as Moshe Safdie’s carbon-churning paradisiacal shopping mall in Singapore Airport.

Let me end this essay, then, with a necessarily partial sketch of some of the shapes and styles of wild capitalism in the time of PPParadise, which brings together the arguments enumerated in the pages above; as well as pointing to some potentially fruitful areas for further inquiry. Although wild capitalist PPParadise is especially well-articulated in Moscow – where the power vertical and political centralization endow the futurity of Zarydaye Park and the grandeur of the blagustroistvo regime with a particular vividness – it is not useful to comprehend it, I will argue, as only a Putinist peculiarity. PPParadise flowers atop the ruins or the decayed remnants of modernity (whether in the form of demolished Khrushchev-era hotels or 19th century railway lines); although its posturing is rhizomatic (and anti-monumental, horizontal), PPParadise is in fact utterly arborescent: monumental in its anti-monumentality, structurally reliant on vertical supports (in the form of patronage from political and financial powers-that-be). PPParadise is underpinned by grandiose acts of sovereign gifting – but the benevolences are commodities masquerading as gifts, and they are given and received not only by sovereigns and citizens, but also by corporations, real-estate speculators and philanthropists. PPParadise is nominally public, but it is owned and managed by public-private partnerships or non-governmental actors; and its terrain is hierarchically segmented into numerous gradations of access and affordability (segregated primarily according to wealth, race and bodily ability). The rhetoric and aesthetic of PPParadise is resoundingly ecological – but much more resounding than its ecological rhetoric is its carbon footprint. PPParadise thrives on a tirelessly-articulated commitment to a theatrical type of expressiveness and affective intensity, which is “pathless”, “free”, “wild” and “spontaneous” – but this wildness is highly sanitized and controlled; and it is regulated, directed, choreographed, recorded, quantified – and enabled – through and by a regime of sonic and scopic surveillance (and self-surveillance), which is as pantocratic as it is panoptic. PPParadise’s “wild urbanist” disciplinary arsenal is composed of a dazzling array of low and high, top-down and bottom-up technological devices. In the case of Zaryadye, this arsenal encompasses pigeon-policing birds of prey, battalions of state and private security guards (both uniformed and plain-clothed), three hundred muzak-booming loudspeakers and dozens of centrally-controlled security cameras; but it also relies on the assumed (and proven) theatrical narcissism and grassroots docility of its users, whose geolocated social media posts are recorded, sifted through and logged by the park administration and municipal authorities. On the surface, PPParadise looks almost the same wherever it is – but it always makes room for local inflections, nationalisms and aestheticizations. PPParadise is planetary, but it cannot be everywhere – it is wasteful and expensive, so it tends to exist in its full flowering only in the very centre of colonial metropoles, whether Moscow, London, Dubai. Singapore or New York – but it is always built by precarious migrant labour, distinct from its users in class and race.

Frederic Jameson extrapolated his political economy of capitalism by looking at buildings – most famously the Westin Bonaventure Hotel in Los Angeles. As Jameson pointed out, because of the expense it entails and its connection to land values, the relationship between architecture and economics is “virtually unmediated … of all the arts, architecture is the closest constitutively to the economic.” The good thing about architecture, in other words, is that you can see capitalism very clearly in it, especially if you look only a little bit beyond its surface. If you look at architecture today, all you can see is paradise and luscious wilderness. Overturn a few rocks, pick a few weedy plants, rip out a few clumps of turf, bribe a few officials, and you will find a pyramid of sorts.

10. Boris Kagarlitsky. 2007. “Reactionary Times”. Chto Delat No. 15: https://chtodelat.org/b8-newspapers/12-59/reactionary-times/ [accessed 12 March 2020]. I. thank Denis Stolyarov – who submitted a PhD thesis on Russian art in the age of wild capitalism to the Courtauld Institute in February 2020 – for drawing my attention to this quotation.

11. On the links between the images of Pantokrator in Orthodox churches and the Bentham’s Panopticon, see Simon Werrett. 2008. “The Panopticon in the Garden:Samuel Bentham’s Inspection House and Noble Theatricality in Eighteenth-Century Russia.” Ab Imperio 2008 (3): 62.

12. See the description of Alexey Korsi’s work “Presentiment of Love” in Kravchuk, Daria, and Michał Murawski, eds. 2018. Portal Zaryadye (Exhibition Booklet). Moscow: Institute of Zaryadyology/Shchusev State Museum of Architecture, pp. 42-43, https://www.michalmurawski.net/zaryadyology [accessed 12 March 2020].

13. See Frederic Jameson. 1991. Postmodernism, or, The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, p. 5.